We don't make our kids "share." Here's why.

We’re all people-pleasing and I think we should stop

What’s the most ubiquitious command given to children, uttered constantly by parents everywhere and possibly beat out only by the vague command to “be careful”?

Share. You need to share. We need to share.

I don’t like it. Here’s why.

My oldest daughter had just turned three. As her little birthday party was winding down, another girl wanted to take one of her balloons—a unicorn one—home with her. I told the mother I’d ask my daughter. I explained the situation to my daughter, and that it would be nice (actually, I probably said “thoughtful”) to give the girl the balloon because she really likes it, but that it was up to her.

After some consideration, my daughter said no. The girl burst into tears. Though it was tempting to try to talk my daughter into the request (she did have two of the unicorn balloons, after all) I kindly but firmly stood by her decision. We’d picked out the balloons together for her party, and she wanted to keep them. I empathized with the girl’s sadness, and encouraged my daughter to do so as well, but I made sure she knew her that her decision was okay.

Later in the week, we were seeing the little girl again. I asked my daughter if she might want to take the girl the balloon now (it was still going strong helium-wise). This time, she said yes. We talked about how kind that was and how excited her friend would be. Both girls were thrilled when it was handed over, and it was a joyful morning.

As

(re)published recently, what we generally mean when we tell children to share is that we’d like them to give up an item because another child has indicated they would like it. I’m not saying most parents would have made their kids give a birthday balloon away (would you have?) but it’s interesting how “We need to share!” rolls off parents’ tongues so frequently and seemingly without much conscious thought. Are we worried we’re raising terrible kids? Are we concerned that others will think we’re raising terrible kids?Regardless, I think it’s fair to wonder if this and other similar efforts can be heard as “you need to say yes to what people want from you” or “what others want is more important than what you want” or even “making other people happy / being ‘nice’ is of highest priority.” I hope we can all agree that none of that is what we’re going for.

We all want our kids to be good people when they grow up, but admonishing them to heed all requests of others isn’t the way to accomplish that.

I was listening to an entrepreneur podcast recently, and the woman being interviewed said, “Instead of your default answer being yes, your default answer should be no.”

Her advice makes so much sense: our time and resources are limited, and we need to care for ourselves well first before we can care well for others. My mind was a bit blown when I realized that, even as a pretty independent-minded person, I definitely feel my default answer to any request another makes of me is yes.

It’s 2025, but for many of us saying no to others still feels… challenging. How many people do you know who have a hard time with it? I’m betting more than a few. Many of us struggle to decline invitations, work, activities, etc., leading to lives that are stressful because they’re too full, not to mention our inability to say what we really think or feel (a form of saying no), which creates surface-level relationships and eventually, resentment and disconnection to self.

Despite these bad results, we seem to hold tightly to the idea that we should put others’ well-being before our own, and that anything else is selfish.

And so I have to wonder: when did the propaganda start? How did we so deeply absorb this messaging? I definitely think part of it is growing up in church spaces where teachings like J.O.Y. (Jesus, others, yourself—the proper order of things) are foundational.1 Could it also be that our natural instincts to be ourselves, to take up space in the world and dare to have desires and preferences, were stamped out early by scoldings like “you need to share”?

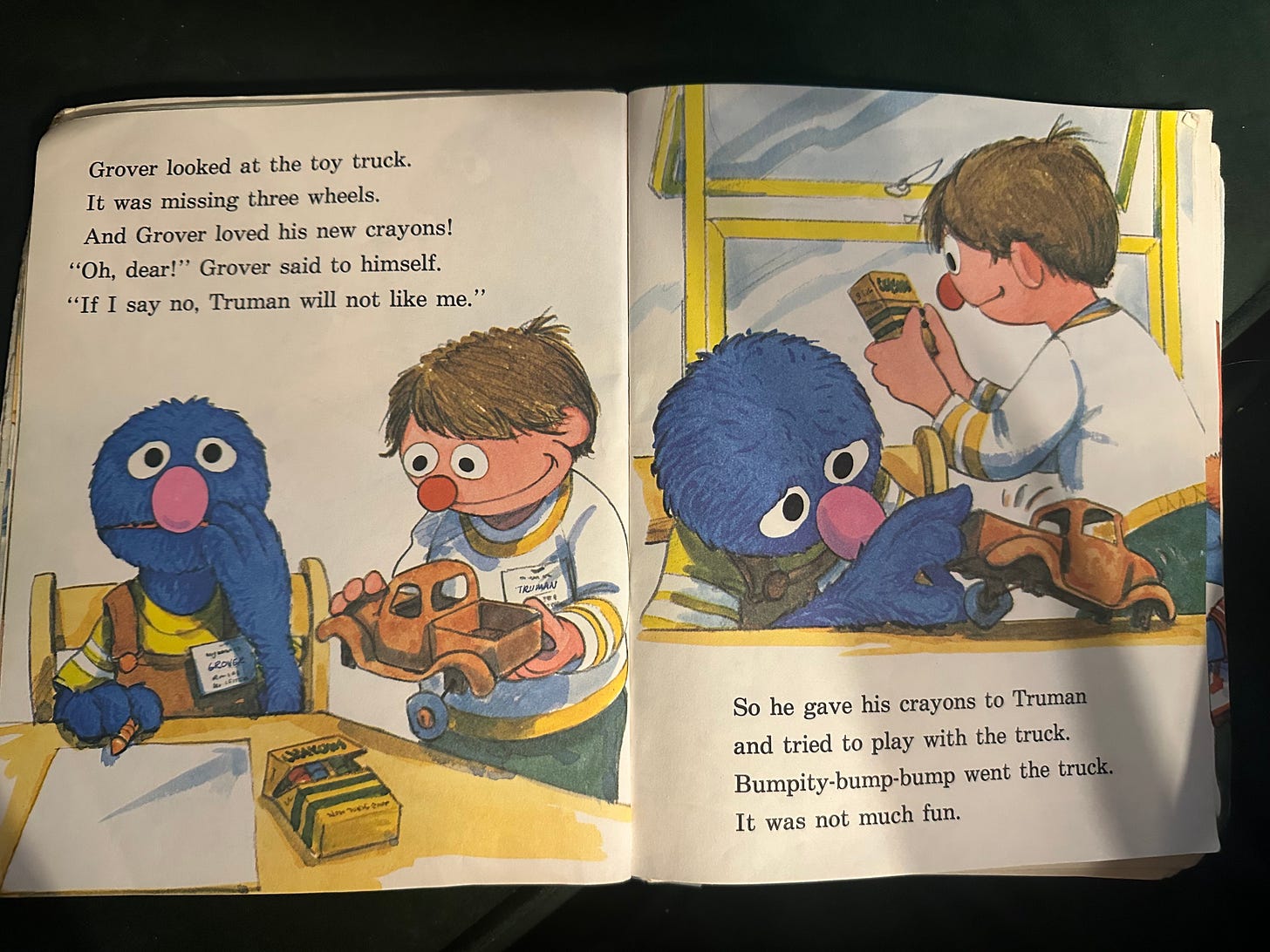

There’s a old, tattered Sesame Street book I came across randomly, innocently titled Grover Goes to School. When I picked it up I had no idea what I was in for. In the best way.

In the story, Grover’s getting ready for his first day at school. He’s a little nervous, especially about making friends. “What if nobody likes me?” he says. His mother gives him good advice: “Just be yourself. You are very loveable.”

Consumed with wanting everyone to like him, you know what Grover does almost the whole first day of school? People please. He says “yes” to everything anyone wants, and does things for them in hopes that he’ll win their friendship. He trades his nice new crayons for an old crappy truck. He volunteers to clean up from art time so the rest of the kids can get their snacks right away (predictably, no snacks are left when he’s done). He really wants to play hopscotch, but he agrees to turn the rope for jump rope when the kids ask him. He trades his jelly sandwich for a baloney sandwich (and he doesn’t like baloney).

Grover is in tears at this point. His strategy has not worked: he hasn’t made any friends, and he’s having a pretty crappy day to boot.

However, the story ends well: Grover finds another way to be!

A girl asks him to play marbles, but he likes jacks better and he says so. When she replies that she doesn’t know how to play jacks, he briefly cries again (maybe his new way of saying what he really thinks/feels is failing?!), but she asks, would he teach her? He’s thrilled to do so. Then, a boy asks him to trade pencil boxes. He thinks, and then says no. The boy is fine with it, and also, he loves jacks too!

All three of them play jacks after school, and Grover comes home and excitedly tells his mom he made two new friends. (“Being friends with everyone” which was his goal at the beginning of the book. Barf.2) “Two new friends?” his mom says. “That’s a lot!”

It’s… wonderful. Alternative titles: Grover Gains Self-Respect. Grover Learns Boundaries. Maybe those wouldn’t have resonated in this little book’s year of publication (1981). I like to imagine a clever writer or editor trying to sneak some emotional intelligence into American homes with such a seemingly innocuous title as Grover Goes to School!

Grover’s mom told him he was lovable just as he was, and that’s exactly what kids need to internalize. They don’t need to learn to earn love by pleasing others. Instead of over-emphasizing that kids share (and listen and be nice, the most common directives given to kids—and all other-focused, you’ll notice), we need to add a grounded, confident sense of self-love and self-respect to what we’re trying to develop in our children.

Should we teach kids to be considerate of others? Absolutely. But parental direction and books on that abound. What I think we really haven’t thought about enough is how to teach kids to be considerate of themselves. We need both.

The title of this post—"We don’t make our kids share”—is obviously a little clickbait-y. Of course we teach our children to care about others, but we try to do it in a way that doesn’t (even if inadvertently) teach them that they/their needs/their preferences don’t matter in the face of what others want.

A few thoughts about what this looks like on the ground.

On an uber-practical level, I get it: it’s hard to watch kids be hoard their toys or not be as “giving” as we’d like in a social situation. But we seem to have very little concept of child development and think behavior like that reflects on our parenting or means something is wrong with our kid. It (largely) doesn’t. It’s normal. Children who do these things are not terrible or headed down a friendless, selfish path; they’re just growing people figuring it out, acting in ways that are probably developmentally appropriate.

Regarding how to support these situations, I like what Daniel Tiger has to say: “Find a way to play together.” I find myself using phrases like that a lot, trying to trust in children’s creativity and problem-solving capabilities. Another alternative: just letting them be. As Janet (the queen) lays out in the aforementioned post, we are often ascribing meaning to situations like this that are not actually present for the kids, and they learn a lot from what happens in social interactions.

To be clear, I’m not gentle-parent-script-ing anyone. This isn’t about banning the word “share,” just like I wasn’t saying we should never tell our kids “good job” in this post from last year. (I do say “we need to share” sometimes, like when a kid is waiting for the swing at the park.) This is a(nother) reflection on why some things come out of our mouths as parents so very easily, what that might mean and how we might be more thoughtful.

Because the thing is, children are learning how to be people in these little years. How we direct their behavior—and what we model for them—is powerful. I look around at the rampant people-pleasing (not to mention the terrible mental health of so many), and I just wonder about the messages we get in these tender years of our lives. I wonder if repeatedly telling children that they must immediately heed the requests of others helps teach them that what matters most is other people, that we are to always set ourselves to the side.

I don’t know, but I’m personally choosing to watch it in this area. I don’t want my kids to have to learn as an adult, as I did, that things like stating my preferences or declining requests are totally okay things to do.

So yeah, I don’t loudly proclaim “we need to share!” when a conflict over a toy arises. People can think I’m doing it wrong if they want to (and they do). That’s okay. As I wrote in my recent piece at Verily, one of the biggest things I now understand as a mother is that I will not get recognition or applause for much of what I do. This is helping me in so many ways, including—YEP—learning to notice the strong desire I have for others to like/approve of me. As I heal from this pattern, I’m increasingly modeling for my kids what I believe is a healthier way of being.

I think “we need to share” is a signpost of our collective addiction to people-pleasing. Maybe it’s not and I’m totally overthinking. What I do know is that we need to become conscious that trying to earn love and belonging by making others happy is a futile endeavor, that it’s fundamentally a self-abandonment that will not bring the desired results.3

This is difficult work. But, like Grover, it’s a happy day when we realize the world doesn’t end when we tell people no. Not at all! Instead, we build robust relationships and we maintain our self-respect in the process. I think this really matters.

I wrote much of this essay about five years ago. It sat in drafts after I couldn’t find it a by-lined home, and I remembered it recently after a conversation with someone on this topic. I welcome your respectful thoughts, always!

P.S. If you resonated with this post, you might enjoy this one from the archives:

Childhood is not a performance

“There is no single effort more radical in its potential for saving the world than a transformation of the way we raise our children.”

P.S. In case you missed it, I’m feeling inspired to get back to my book proposal, and if you’ve liked my writing, I’d love you to become a full subscriber at 40% forever. Sending a few bucks a month my way ($2.50 specifically) is the best way to tell me you think the things I’m saying matter. It helps support my family, and it’s a huge encouragement to me to keep prioritizing writing!

Made me so happy when I heard a talk last year by one of our priests that said the proper order is actually God, yourself, others. THANK YOU. Ah the ways I’m scarred from my Protestant upbringing lol

I find a lot of children’s books are like this… annoyingly preachy and messages adults never could/would live up to

And instead will bring anxiety and depression

I’ve been noticing lately that I’m more tempted to tell my child to share just to make the other one stop whining. Which is…entirely unhelpful and dysfunctional for everyone! But the desire for immediate peace when I am overwhelmed by the noise is strong enough to make me lose my wits at times! More fundamental than generosity is understanding that I’m not entitled to anything and everything I want, immediately, even if it’s not mine. I’ve been trying to slow down and focus on that.

Great post, thanks for dusting it off for us!

Thank you for this thoughtful piece. I want to share two thoughts. 1. There is a difference between sharing as you define it RE the balloon and taking turns. I would never make my kid give up that balloon, and in fact, I’d be mortified (and give him a talking to) if he asked for a balloon at someone else’s party. The person in the wrong there was the other girl’s parent, for even entertaining that inappropriate request. You don’t get to take what belongs to someone else: that’s not really sharing; it’s a kind of seizing lol. But I do, as you point out, absolutely require that my kids take turns. On a park swing, with a toy if they have a friend over, etc. Because that is social grace/good manners. 2. I do not have girls. If I did, I’d err more on the side of less social grace/less people pleasing because I think they get that messaging enough elsewhere, on top of being, in many cases, more agreeable to start. With my sons, I am at baseline less worried about it. In part because none of them is particularly agreeable in that way, and in part because I am more worried about them not being jerks haha. That said, this is some really good food for thought. Because even though this remains the case, it is also true that my most naturally willful one is also my most empathetic/politically astute one, and so it is really important for us to keep an eye on this as he gets older — especially, I think, once he starts having more interactions/relationships with girls.